Veridian

A six-lettered monument to loops & waveforms.

There’s a short interval of flight in which birds’ wings are tucked into their bodies, imprinting the air briefly with a more ovoid impression akin to dolphins or badminton projectiles. (Shuttlecocks, I guess they’re called.) In contrast to avian parabolas and disregarding variable topography, elevators, staircases, and actual planes, I move upon abstract planes, mostly, confined to two dimensions, paved horizontal slices of the world. With no wings to untuck, the only sensorial access I have to a rapid shift in Z-axis comes from trampolines, from falling into water.

One quirk of two-dimensional computer games is in the primacy or absence of simulated gravity. It’s so obvious as to be rarely called out, but 2D games actually fall into distinct subtypes: 1) top-down planar play and 2) vertical slices. Physical tabletop games transpose neatly to the first, but many of our richest digital environments are actually just upright cross-sections which can’t translate as cleanly backwards to reality for obvious reasons (as much as I’d like to navigate a skyscraper partitioned like a loaf of bread). Another way to think about this is that gravity is a feature of 2D simulations sliced vertically, while horizontal slices are simulations in which gravity is a non-factor. Confusingly, there’s a square-rectangle logic here, as this condition holds for virtually all platformers but rarely for horizontally-scrolling shoot-em-ups: perhaps 2D games with gravity are vertical slices, but not all vertical slices have gravity. (A handful of particularly complex 2D games break this rule by simulating gravity between horizontal layers, such as Dwarf Fortress.)

Exceptions aside, take this taxonomy further and locate another subtype of 2D games, one in which gravity is neither absent nor fixed, present but conditional. VVVVVV (2010), which has been on my to-play list for fourteen years and which I recently completed in one sitting somewhat accidentally, is a game with three inputs: move forwards, move backwards, and flip the direction of gravity.

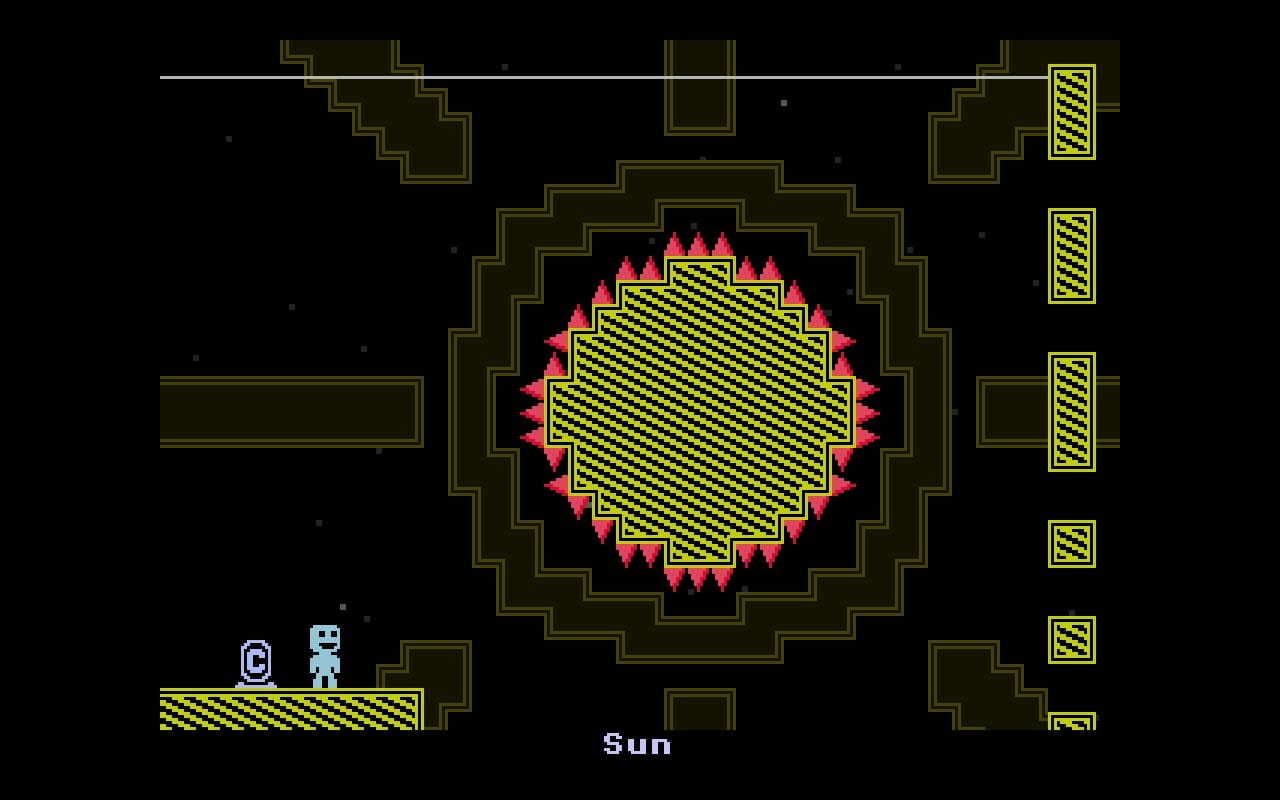

Mind you, the game’s title is in one sense narratively acronymic: one V each for six crew members–Violet, Victoria, Vermilion, Vitellary, Verdigris, and our own avatar, captain Veridian–who have been separated during space travel by some kind of dimensional interference, stranded within a highly abstract, voidlike environment of monochromatic polygons. Gameplay takes place (mostly) within a 20x20 grid of rooms which might be individually entered and exited with traditional platforming logic, but more notably by falling up. The main trick: you cannot actually jump, only reverse the direction in which you tumble. Less platforming than oscillating! And hence the real meaning of the six-letter title, a clever visualization of the sinusoidal waves traced during the game’s strange method of movement. (I wonder if there’s an esoteric label for this eytomological quality, which I’ve only otherwise encountered in the very bedframed impression formed by the letter order of “bed”?)

VVVVVV is a label & game of waveforms, but also of loops: in certain sections its two-dimensional space wraps around three-dimensionally back upon itself, with the ceiling connected to the floor. Traversing from the left side of the screen to the right in such places involves falling forever–until it doesn’t–and it’s with this Möbius strip mechanic that the game’s strangest quality becomes most discernible. You can only ever fall instead of jump, but since the “ground” is being constantly redefined, here is a game in which the player has both local and omniscient control–the act of a jar being turned over but also the movement of an insect trapped inside it.

This kind of slippage strikes me as uncommon. Typically, computer games in which you have some kind of environmental or macro control involve the use of commands–you tell affected entities how to behave, rather than control them directly. Likewise, games in which you instead control an avatar enable a delegated influence over their environment: when I say “I” threw a bomb at destructible tiles, or “I” unlocked a door by bringing a key to it, I’m really referring to acts which are mediated through the inter-agency of a player character, e.g. Veridian. No such mediation here: gravity on one hand and lateral movement on the other (literally, when using default controls). If I could name a disappointment with such an otherwise intricate mechanics cocktail, it’s that its fascination is more with kinetics & reaction time than puzzles & parity; gravity-flipping only ever applies to our chrome-green protagonist, so movement is a lot less existentially fraught than than it might be otherwise. In any event, one begins to imagine games which likewise blend movement with other conditional laws of physics, or which likewise defamiliarize actions, like jumping, we take to be bound to those laws. A variable speed of light, a binary switch for entropy.

Anyway: this queasy mediation reverberates elsewhere. Level screens are affixed with charming title phrases, e.g. an exhaust pipe-like tunnel called “EXHAUSTED,” which grants a flashcard quality to falling between them. Aided by the overall minimalist aesthetic, these quips form a central allure of this game, which is the ability to quickly memorize & navigate the strange topsy-turvy sequencing of the game’s mazes by forming non-spatial associations with abstract places–traversing through a room, but also through a joke about its shape, an elicitation of its general vibe. The hardest area (by a long shot) is a seven-screen sequence which must be ascended and descended without a checkpoint, three of its screens appropriately titled VENI, VIDI, & VICI. If the choice of where and when, precisely, to fall from and to, is a decision that involves multiple ontological layers of the simulation, then the structure of the game itself reinforces this layering of perspectives.

Fitting, then, that upon conquering the game’s campaign, a marvelously structured postgame unfurls for particularly curious players: collectibles, time trials, an ultra-hard iteration of the “gravitron” minigame, and low-death count challenges. Each of these categories incentivizes players iteratively, since success in locating all the collectibles in previously visited areas will teach proper time trial technique in them, which informs the challenge runs, and so on. It’s a small detail, but I’m also very fond of meta achievement systems existing diegetically within a game’s world, and the laboratory’s trophy room here is as good an implementation of this as I’ve come across: rewards which rupture the boundary between the digital marionette and the human controlling its strings.

Perhaps the most appropriate gauntlet is the option to play the entire game with the map flipped upside down, another kind of defamiliarizing gravity switch. I’d only otherwise seen this trick in 1997’s Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, one-half of the metroidvania genre portmanteau for which we’re beholden decades of nonlinear platformers (like VVVVVV) with utility-gated progression (unlike VVVVVV). Of course, Veridian’s is a more abstract game about verticality than Alucard’s, ripe for upending, but it’s not like anyone cared about the internal consistency of Dracula’s castle being flipped: skilled players simply want challenges which demand the game be played in new ways–that games not so much end as begin anew upon completion, wrapping back upon themselves.

So: a second square-rectangle game genre rule for you in closing: not all metroidvanias are nonlinear platformers like VVVVVV, but far too many nonlinear platformers are metroidvanias. It’s a genre I adore but one which I’d also like to see us move on from, truthfully: the MV dictum that certain doors (abstract or otherwise) remain locked until the player finds a key (ability or otherwise) limits the permutations of exploration by default, as such utility-gating often means being guided tepidly between a sequence of objectives that, while nonlinear, remains fixed, or else backtracking between dead-ends. At its best, the genre’s worlds feel like intricate, living labyrinths, but regardless of the genre’s other origin point being the sequence-breaking Super Metroid, Metroidvania games often restrict exploration, not enable it. Nothing reminds me I’m interacting with an arbitrary computer program like running into an arbitrary boundary. VVVVVV is, in contrast, extraordinarily open, its five central objectives reachable in any order. This quality augments its bizarre and captivating sensations of momentum even before you turn it upside down to begin again, oscillating through the void like a bird.