UFO 50

2024's most unlikely open world computer game offers a kind of world tree for the interactive medium.

I've felt unusually obligated to evangelize UFO 50, not only because I've already played Mossmouth's compilation of retro- and arcade-style games for 70 hours in three weeks–yikes–but because I feel deeply that it is both a monumental achievement in the history of computer games and itself an encapsulation of much of that history. I suspect that at this point we barely understand it. Achievement statistics at time of writing puts my bender around the 99.6th percentile of the player base, and although there's a third of games I've normal clear-ed there's a third I haven't touched. Nobody has scratched the surface here.

UFO 50 is an impossibly generous and varied creative product. As a compilation of individual games, its standout quality is to offer an exciting riff on or blend of genres that in most cases were prevalent on the NES/Famicom and other third-gen 1980s consoles. Many of these genres arose out of hardware restrictions which no longer exist, which instead operate here as voluntary creative constraints, like when a contemporary director or author of fiction opts for film over digital, or longhand over a word processor, because these processes are so latently valuable to and inextricable from the best historical results within their mediums. Constraint as the closest friend of the artist. As I understand it, there are tons of platformers on the NES because the hardware memory can only hold so many sprites. The clouds in Super Mario Bros. are the same sprite as the bushes, flipped & recoloured, but the system was great at rendering multiple enemies/projectiles moving on the screen. Contra, Mega Man 1-6, Castlevania 1-3: the NES was made for this stuff. And so too, is (fictional) developer UFOSoft’s (fictional) LX console(s), whose (very real) catalog has been consummately created and curated with a staggering blend of these constrained historical genres reconstituted through all manner of contemporary indie design philosophies.

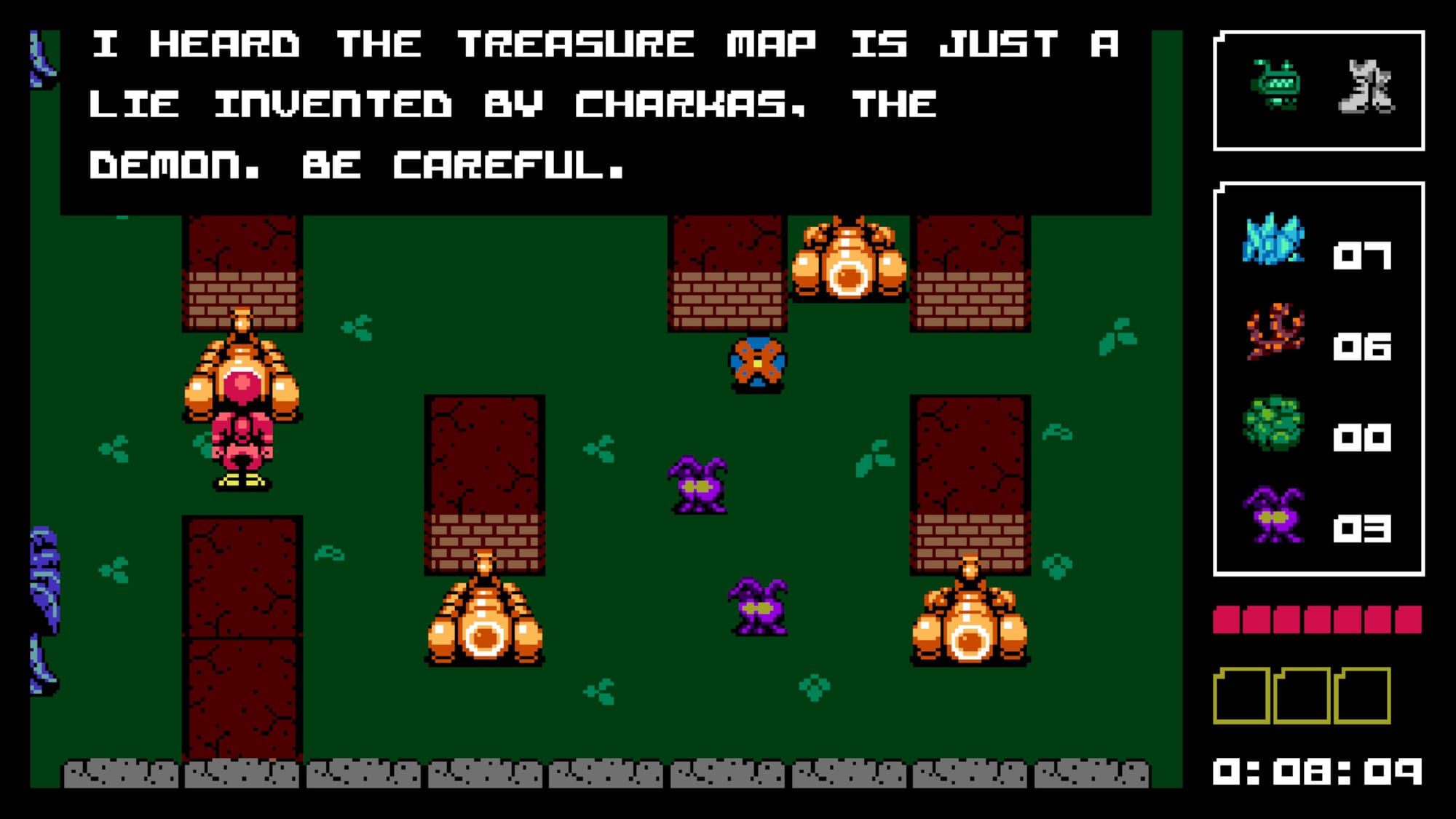

UFO 50 is an interactive canon, self-contained & -constrained to two dimensions, thirty-two colors, and six inputs: a directional pad plus two buttons. I don’t know if you’ve actually played The Old Stuff, but the original Zelda or Metroid installments hold up *despite* comparable hardware limitations, not always because of them. The allure of UFO 50 is to retain the purity and strangeness and tight craft of such titles with an eye for experimentation, for tweaks which I would prefer to describe as “mechanically informed” instead of “quality of life fixes"–the latter implies a kind of concession to modern design sensibilities somewhat antithetical here. Game #12 Avianos looks like the original Civilization, but it features charming autobattle mechanics likely impossible in the 80s. The roguelite-y, mid-level store mechanic which is occasionally superfluous in our own era is a glass slipper for a tight arcade gunner like #7 Velgress. #4 Paint Chase is Splatoon by way of Pac Man. #22 Porgy is not unlike a 2D Subnautica. These games may look old but I cannot stress enough how novel and refreshing they each feel interactively: shmups, deckbuilders, dungeon crawlers, tower defense, sokoban, tile-based strategy, metroidvanias, golf–it’s very rare that a title here taps only into one genre, and if it does, it still features a mechanic which is fundamentally novel to the lineage of titles for which it pays such precise homage. #8 Planet Zoldath might initially read as a modest riff on the original Legend of Zelda, but its randomization will come, upon closer study, to reveal a deep game in which ability-and-item-gated exploration and dialogue is shuffled wildly upon every reset. In one instance you might need the translator to speak and trade with orange scorpions which in another instance will attack you outright. The best word we have for this kind of gameplay is emergent: complex situations arising out of the interaction between simpler elements. The trickiest thing about emergent or otherwise experimental design: it *looks* the same as anything else.

UFO 50, launching itself above layers and layers of industry nonsense around livestream potential, general marketability, financial return, photorealism, concurrent player counts, and all kinds of other corporate bleed into creativity, is a radical reminder of a more stable hierarchy between a) gameplay and b) everything else. Visuals matter as much as sound design, and shiny million-copy GOTY contenders are always, like, fun, as vague as that word may be; a non-mutually exclusive observation is perhaps that graphical fidelity and even art direction never actually take precedent over a foundation of solid mechanics. Put it a third way: interactive depth is not something that translates cleanly over text blocks or Twitch streams or screenshots. I think it's difficult, without playing it, to understand just how contingent the more filmic aspects of something like The Last of Us: Part II is upon a highly varied, and highly brutal, survivalist loop of third-person cover shooting with resource scarcity & crafting. Something visually simpler, like Tetris, has in contrast now worn so many dozens of styles that it’s easy to forget how much mechanical complexity arises out of its 40-year old rectangular purity. Super Metroid randomizers, with their 32-bit sprites, are surely more popular than speedruns of Metroid Dread, with their 3D models. Pixel art is a vibrant visual form in and of itself, but there’s a reason Stardew Valley can exist due to the work of one person and still sell as well as any of Sony’s first party offerings throughout the last decade, each of which required the years-long coordination between hundreds of salaried artists, engineers, corporate pencil-pushers, and various contractors. Make no mistake, I love AAA games and play plenty of them. But that space is about to (or already has) entered a death spiral for which my (total outsider) hypothesis is some kind of confluence between corporate mismanagement, trend-chasing, and, mostly, an arms race for visual fidelity which has had diminishing gameplay returns for multiple console generations. Color me unsurprised if Nintendo continues to dogwalk this entire industry with objectively worse hardware merely because their philosophy allows “small” (40-60 person) teams to execute, experiment, and iterate upon projects with vastly lower visual fidelity which side-step resource drains like filmic narratization or GAAS nonsense in favor of simple, punchy design. (It's no coincedence that game of the decade shoe-in Elden Ring boasts a gameplay loop that is ultra-non-interruptive, and it's no coincedence that contender Baldur's Gate 3 is a direct ancestor of tabletop-roleplaying titles whose addicting mechanical complexities become more manageable when a computer does all the behind-the-scenes DM work). In sum: if graphics aren't the determinate factor of critical and commercial success, why does a game like Captain Toad’s Treasure Tracker outsell Concord? Because one of them had to sell millions of copies in order to succeed at all, and so was driven, from its earliest stages of design, by such profit matrices.

UFO 50 offers what I have come to crave and cherish as ~nothing but the game~, or, in this case, nothing but fifty of them. I manifesto-ize all of the prior paragraph because I think it’s crucial to play UFO 50 with an eye for how utterly careful and utterly intentional its many gameplay *mechanics* are in the context of a gaming landscape which has become hyper-distracted and polluted by non-artistic considerations. Now, the sprite art in UFO 50 is wondrous, and I’ve been screenshotting bizarro title cards and level elements like crazy, but I play a visually-simple game like #23 Onion Delivery for 4 hours because Onion Delivery is impossibly fun on a moment-to-moment basis, because it never lets anything get in the way of what it was intending to be, interactively.

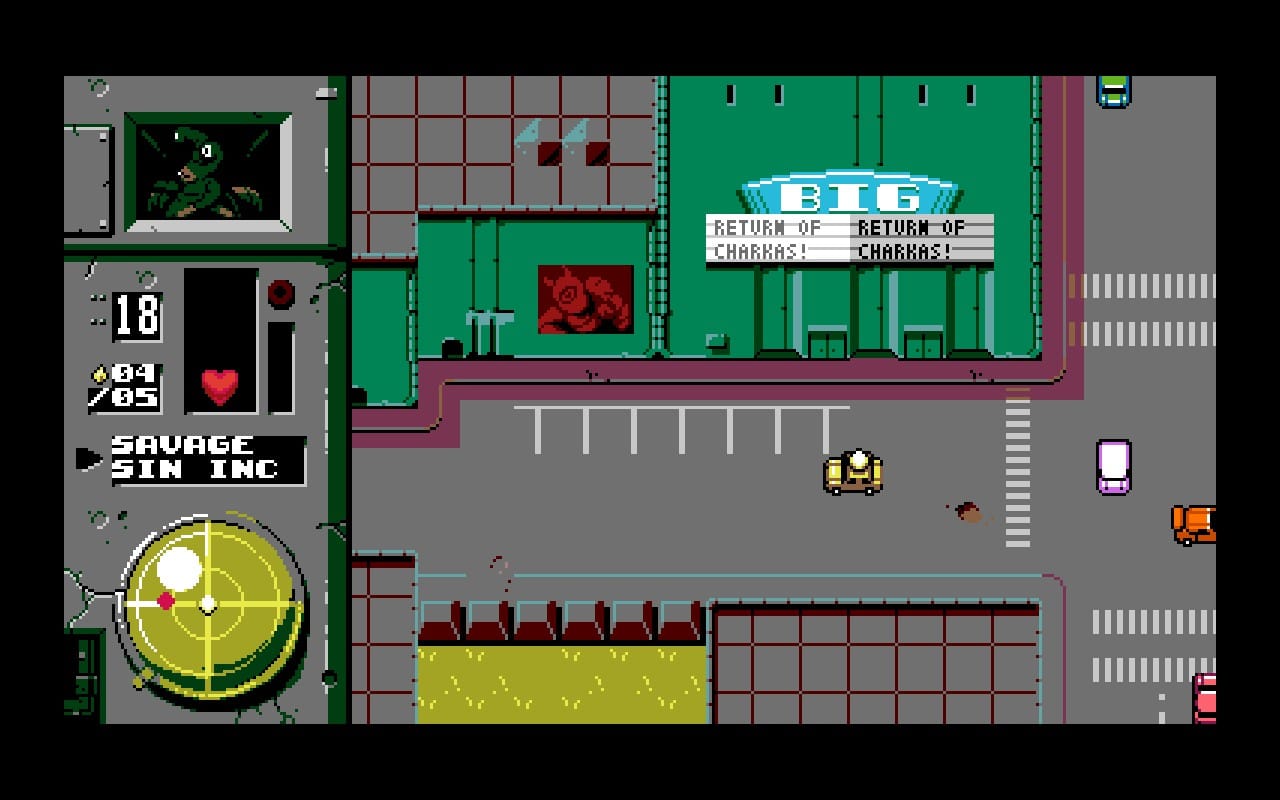

UFO 50 is intentional. I mention Onion Delivery specifically because every time I have suspected one of the fifty games here to be stupid, or underdeveloped, or retrograde, it surprises me with dynamic mechanics that I was just too impatient, too stupid, to learn initially. Onion Delivery is a game in which you Uber-Eats onions to tentacled urbanites in a backwater alien metropolis while avoiding level modifiers like storms, floods of slime, zombies; its top-down frenetic driving controls (a la Grand Theft Auto 1997, I'll have you know) will demand some time, and feel frustrating at first, and reward that mastery in kind. I could list dozens of microdosed epiphanies here, about tapping left only once to switch lanes, or realizing the level actually loops upon itself, or memorizing alleyway hairpins based off of landmarks which exist more sturdily in my mind than they ever do on a rapidly-scrolling screen. The close-call non-collisions, the garish city's strong sense of place. I adore this game in part because of how surprised I was to find it adorable, because of its uncanny blend of charming surprises and deceptively nuanced controls. And yet it’s only one of fifty games which have likewise been crafted with the same eye for the sheer weirdness, playfulness, and non-normative control schemes of a generation far less conscious of the many past patterns of success. After ten minutes it’d be easy for you to play, and dismiss, any of them–especially this one, since its particular mode (top-down racing) is so fossilized beneath decades of more powerful hardware and newer branches on the family tree of genres and mechanics. After an hour I'd challenge you to dismiss a single one. Surviving a week of onion deliveries is a gaming ~achievement~ I’ll remember more fondly than a lot of the stuff I’ve played over the last five years, and I’ve played to completion a lot of stuff, new and old. I have a lot of love for something as gargantuan as Elden Ring, which playing blind might still eat one hundred hours and change from a skilled player. But Elden Ring is at least somewhat inherently repetitious, especially to those of us that had 500 hours in the Souls series coming into it. Mossmouth is right to advertise the games in UFO 50 as non-minigames, as full experiences, but that framing belies how tight, how focused, each of them are: some of them are "only" 4-5 hour experiences because all of the fat has already been removed. Nothing but new idea after new idea, a refreshing structure which makes revisiting each all the more appealing.

UFO 50's quietest success, then, is that each of the fifty games in this collection can be *played* near-immediately, with no cutscenes, tutorials, or non-interactive sections of any kind. There is ample room for deep strategic thinking, for cross-game-connective lore, easter eggs, secrets, and meta progression, but none of it is passive, and your enjoyment will never come at the cost of a controller-down spectator session in which all mystery and exploration is signposted for the player. These games are aesthetically charming as hell, but the thing about their visual spareness is that it allows for mechanical complexity: all signal, no noise. Handholding is antithetical. Learning mechanics for yourself, basic or nuanced, can be–should be–a wonderful moment of epiphany that none of these games *ever* steal from the player. Just figuring out how to *jump left* in #13 Mooncat feels like one small victory of the thousands available here. If you want to look stuff up, be my guest, but this is a game designed, with great love, for those who would rather have the joy of figuring things out for themselves. They are not obtuse. They are just actually games, rulesets applied to interactive environments for which the satisfaction of learning those elements firsthand has been preserved consistently and beautifully.

UFO 50 is, as such, not something everyone will want to play. I can understand why some ~gamers~ don’t have much room for a design philosophy that rewards careful attention, high-skill play, and engagement with a huge variety of ideas that have been sidelined by decades of open worlds, mocap cutscenes, and in-your-face tutorials. There are games here which test your tactical thinking and games which test your reflexes and games which test both. Very few of them are “easy” in the contemporary sense of the word; none of them have ray-tracing. But approximately zero of them are passive, or unfun, or unoriginal, or lazy, or ugly. Better: the joys of mystery and discovery become recursive when the same patterns or elements are reproduced across genres and in-game worlds. You’ll be as happy to see the coffee mug power-up in #17 Campanella as when you first came across it in #3 Ninpek. The jumping purple alien in both of those games likewise becomes a familiar face, cross-connective worldbuilding in the form of carefully shared elements. These aren’t repetitious or lazy reproductions, but intentionally shared nodes within a quilted history of development *between* games which unfurls as marvelously as any of their isolated levels. I cannot really even put to words the experience of finding the red Campanella ship sprinkled across the catalog, or slowly learning about a certain demon antagonist that’s referenced or fought across titles, because for me this fictional tapestry has repeatedly elicited a kind of magic for the soul that I think is traditionally relegated to nostalgia or nature. UFO 50 is, very confidently, actually its own singular open world which you explore by playing not one but each of its titles. The wonder of the collection is that its entries exist necessarily in the context of each other. I don’t care to tell you about my favorite or least favorite titles. For me they’ve already become inextricable.

UFO 50 is very obviously greater than the sum of these parts. The thing about releasing fifty games simultaneously is that the risk of experimentation is drastically lower: many of these games would not survive the games market as singular releases, an opportunity Derek Yu, Jon Perry, & the rest of the team seem to have taken to heart from the very beginning. Conceptualize a herd of trojan horses. Maybe you’re someone ravenous for the non-mainstream stuff that has actually survived throughout the last couple decades, for Moon Remix RPG Adventure or Molok-Syntez or Devil Daggers or Void Stranger or Ikaruga or Rain World. If you have any hunger for an interactive canon which excludes the latest CoD in favor of Spec Ops the Line, or Ori and the Blind Forest for Axiom Verge 2, I am begging you to purchase this game for yourself and for every one of your friends. But the thing is, even if you don’t have any inherent love for the weird stuff and the old stuff, I suspect there has never been a better intro to the possibilities of the medium than just picking up UFO 50 and seeing what fits. My final hyperbolic wonder here is the way this game has become a kind of mirror for my own ravenous movement through the interactive canon. It calibrates to the genres I know–action platforming, grid-based tactics–and to those I don't–vertically-scrolling STGs, first-person DRPGs–with a robust sense of curation, demanding I more closely consider the latter precisely because of my contextual preference for the former. Now: visual & sonic elements have a crucial relationship to mechanics, but I have come to think of videogames as essentially something non-teleological, something that only exists in your mind. If that’s the case, the games in this collection will, if nothing else, act as trigger points for whole swaths of mental journeys that you had no idea you were interested in taking. As someone who keeps an assiduous log of everything I’ve ever played, notes and spiraling recommendations and completion logs and 1CC hopes and so on–I would not be surprised if five years down the line, five or ten of my top 25 games of all time are contained within this $25 collection. But I would not be surprised if the others started as spiderwebbed recommendations from UFO 50. Since beginning my binge I’ve already been scouring archived forums and subreddits for recommendations in genres that this game has revealed to me. #24 Caramel Caramel might lead back to R-Type, to ZeroRanger and Radiant Silvergun; #40 Grimstone back to FFVI or Dragon Quest 3; #9 Attactics and #10 Devilition to Tactics Ogre and Advance Wars. A monumental release, surely, but also a kind of world tree for the form itself.

UFO 50 should not exist. I am happily hyperbolic; at the very least anyone could admit that it does not make sense that a product of such consistent creative invention and paradoxically simple mechanics, such robust understanding of what’s preceded it and such overflowing inspiration for what could follow, could ever have been even finished by a team of six people in eight years. I’ll lose no sleep comparing it unironically to the small handful of works across creative mediums and centuries that are comparably, impossibly generous. Engage with it at all costs.