Tatsujin

Two weeks of Toaplan.

Here is an elder genre: shoot-em-ups, a category which technically contains run-and-guns and rail shooters but is used primarily, these days, to refer to scrolling shooters, for which the 2D playing field scrolls automatically while the player mitigates predetermined waves of enemies and hazards.

In the decade between 1983-93, Japanese developer Toaplan made sixteen “shmups,” most of them initially exclusive to arcade cabinets and only later ported to home consoles. Much of what we take for granted about the design of vertically scrolling shooters, that most dominant of shmup sub-types, can be traced back to Toaplan; if there is one reason to follow the development of the genre (and medium at large) through their catalog, it’s surely that they would eventually invent the danmaku, or “bullet hell,” variant, with Batsugun (1993), their crowning achievement and final commercial release prior to declaring bankruptcy. The work preceding that particular title remains no less important, however: Toaplan had already mastered what came to be known in some circles as memorizers, thoughtful shoot-em-ups focused less on reflex-based play than on an intimate familiarity with enemy placement and movement patterns gained over repeat sessions.

Coin-operated arcade games are naturally inclined towards pattern recognition and memorization already, of course, the form itself being structurally distinct from games played at home. Arcade titles typically feature a series of short levels designed to be completable within a single sitting but also attempted repeatedly, with penalties to one’s actual currency directly proportionate to game familiarity. Designers worked within contradictory design constraints: cabinets had to be difficult enough to recoup their operating cost in credits–via quarters, ten pence coins, 100円 coins–but likewise addictive, with a gameplay loop that could be enjoyed by players either hundreds of times, while they fed the machine credits, or else briefly, while they sampled it before moving on.

Contemporary discourse focuses disproportiately on the resultant difficulty of these games, which, viewed in a vacuum through the lens of later design trends, will certainly feel severe. (A minority of actual “quarter-munchers” doesn’t help.) Our focus should be on another natural result of their creative constrictions, one which has outlived the decline and eventual obsolescence of the initial hardware context: gameplay density. Especially relative to later console releases, arcade games are non-interruptive, rarely (if ever) taking control away from players in favor of more passive modes of engagement such as tutorialization, dialogue, cutscenes, menus; they are context-insensitive, with the controls assigned to in-game actions never changing depending on in-game circumstances; and they are concentrated, requiring players to develop and showcase a high degree of reactive and/or intellectual skill through cyclical engagement against fewer permutations of elements, rather than interact more passively with a larger variety of “content.” Not difficulty, but brevity.

There becomes a certain spiraling appeal to this gameplay structure, which imposes upon its addicts a near-meditative tolerance for repetitive experimentation. A circularity: each replayed level a zen-like echo of its prior attempts, every micro-encounter with a specific array of enemies the opportunity to recall one’s previous and future moments spent within the abstract environment. In the context of the scrolling shooter genre specifically, learning the routing through a well-designed game becomes, in an abstract sense, no more or less arbitrary to the mind and fingers than memorizing a piece of complex sheet music on an actual instrument.

And it is in this context that Toaplan showcase themselves to be particularly talented composers. One high-water mark of the memorizer variant, and early shoot-em-up era generally, is surely Hishōzame (1987), released as “Flying Shark” in America and “Sky Shark” in Europe, in which the player guides a blue biplane through a wartorn tropical landscape inspired by Apocalypse Now. There is no better “tutorial” in the medium than Hishōzame’s, a twelve-second introductory section which communicates (without any text) everything the player needs to know to beat the game, the music pausing briefly over a murky river before picking up again as the five-stage gauntlet begins in proper on the other side: a masterpiece in ludic thresholds. The game can technically be beaten in twenty minutes.

Another Toaplan shooter, Tatsujin (1987) takes its title from the Japanese word for one who has attained mastery. To return to our music metaphor: learning a piece is one thing, performing it without error, and eventually beautifully, is another. We turn to shoot-em-ups in large part because their most natural mode of mastery, the “one-credit clear” or 1CC, offers us an antidote to the sickness of arbitrary achievement systems (and thus, to greater sicknesses). To be able to play the entirety of an arcade game with only one credit is not just to engage in a deep interactive dialogue with the artist-engineers who crafted its simulation, to hone through mental & muscle memories an improvised, idiosyncratic performance through the abstract sub-reality upon which they’ve inscribed supra-physical laws, rulesets which turn such a thing into a “game.” The existential value of a 1CC very easily escapes containment within the arcade cabinet, its metaphors–of recovery, and momentum, and flow–proving applicable and practical elsewhere.

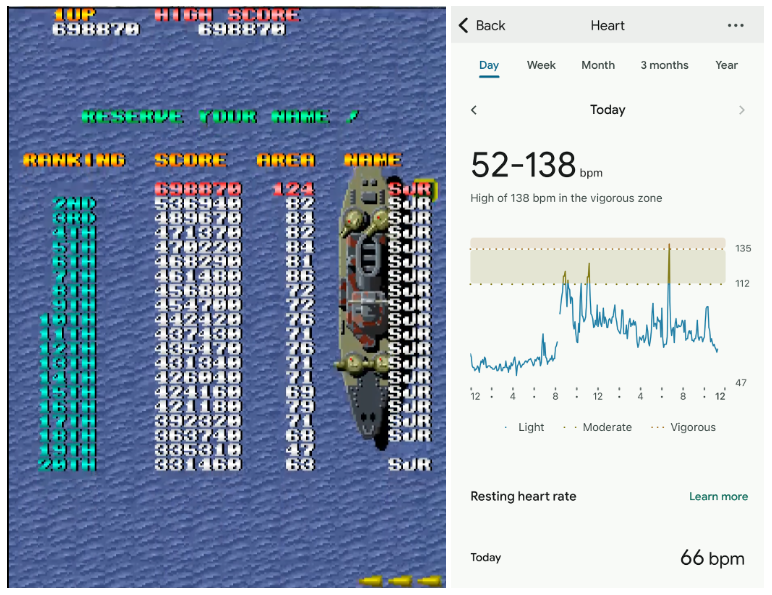

On Tuesday, March 11th, 2025 at 6:38 p.m., my fitness watch recorded a spike in my heartrate, attributable to the realization that I was finally on the cusp of 1-credit-clearing Toaplan’s Hishōzame (1987), a.k.a. “Flying Shark,” a.k.a “Sky Shark,” after some twenty-six total hours of attempts. A categorically “vigorous” 138bpm, specifically, more than twice my then-resting heartrate of 66 bpm and higher even than the other “moderate” spikes which occured during brisk walks downtown earlier that day, a peak which subsided six minutes later when I finally cleared level five without a GAME OVER for the first and only time. It was my momentum & luck during the end of level four, really, a wall of enemy fleets and turrets which had brought me to many a CONTINUE? screen, that lent me the this-might-be-the-one sensation which I suspect athletes or doctors experience more regularly during actual, high-stakes tests of their actual, valuable abilities–balls going into hoops, scalpels slipping up. For me: pixelated biplanes, brother. I was satisfied that I’d been able to 1CC Hishozame within “just” a month, having first played it on February 12th; that my new high score put me at 29th in the world on the PC version’s “single credit no assist” online leaderboard (despite my suspecting this version’s global playercount to be, like, 30); that I could stamp my latest and perhaps final SJR triplicate on the local high score board, a somewhat useless relic of the game’s original arcade hardware.

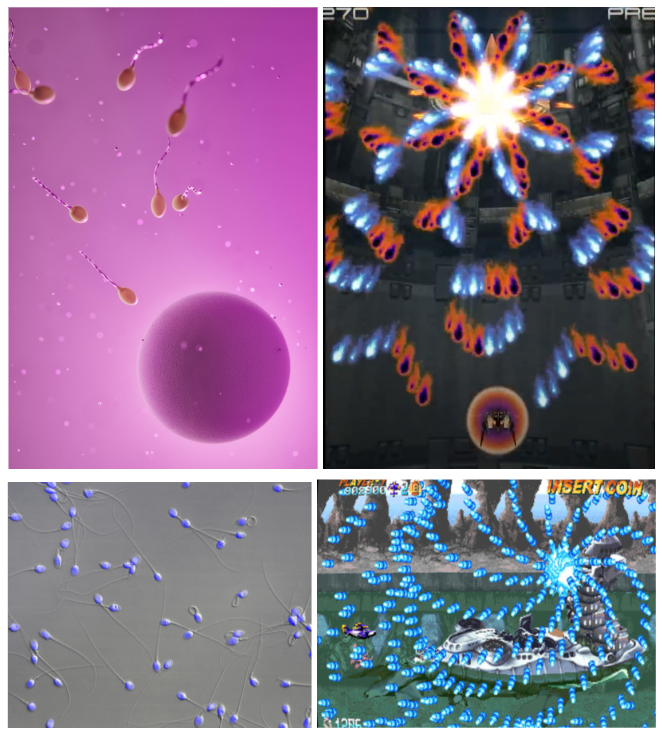

There’s something inherently masturbatory about taking the time to log your own initials on an emulated high score board for which you are the only participant, a hyperliteral act of playing-with-yourself by which post-GAME OVER three-letter tabular input has outlived its raison d'être of in-person competition. Then again, maybe the better metaphor is less one-man than coital, given the inherently sperm-like nature of shoot-em-up games, which interactively restage a decompressed abstraction of the pre-neonatal, pre-uterine microscopic “bullet hell” navigated during a single-cell organism’s existential flight to outpace, via comparably omni-directional projective movement, their bullet-like spermatozoan competitors on the archetypically-scrolling playing field of the fallopian tube. What is your own pre-conceptive fertilization but a kind of primal one-credit-clear?

Any older game emulated on modern hardware loses something tactile and contextual in translation, but the slippage is especially severe for arcade titles, shucked like pearls from cabinets that originally existed not just as imposing physical objects but as nodes forming a communal nexus which once attracted breathing competitors and spectators who remained present, at the very least, through the ghostly imprint of their initialed score entries. It might remain sensible enough to compete exclusively against past and future versions of yourself, but the lonesome ritual of marking (numerously infertile) 1CC attempts on a hermetic-ally sealed score table becomes, at best, an odd gesture towards a place which no longer exists, like carving “SJR” on a framed photograph of a tree. Given a digital version of any one of these titles doesn’t take all that much more space in megabytes than a digital photo, you could fairly reasonably store tens of thousands of arcade games–i.e., all of them–on a single computer, pearls strung up and glittering long after their shells had been collected, shucked, and abandoned, the rows of flickering arcade hardware submerged in a trench of memories that you may not have even experienced firsthand. That one can choose to revisit and play nearly any specific title is a luxury never afforded actual arcade-goers.

So, too, a certain depth of engagement. In 2025, given my shmup 1CC attempts were not subjected to pesky barriers to entry–like, e.g.,“going out in public” or “sharing"–one tradeoff was that I was able to play these games for hours at a time uninterrupted. I found this slice of the medium not particularly well-suited to the gaming binges to which I’m well-suited, however, as the resultant ocular fatigue and wrist pain was fucking insane even by an addict’s standards. Following a couple of three-hour Hishōzame sessions, my left eye would intermittently spasm for the rest of the evening, trying to rock itself out of the socket, and the thumb and pointer finger on my right hand–used for the fire and bomb buttons, i.e., the only buttons–felt as if I’d been using them to hold a binder clip open all night.

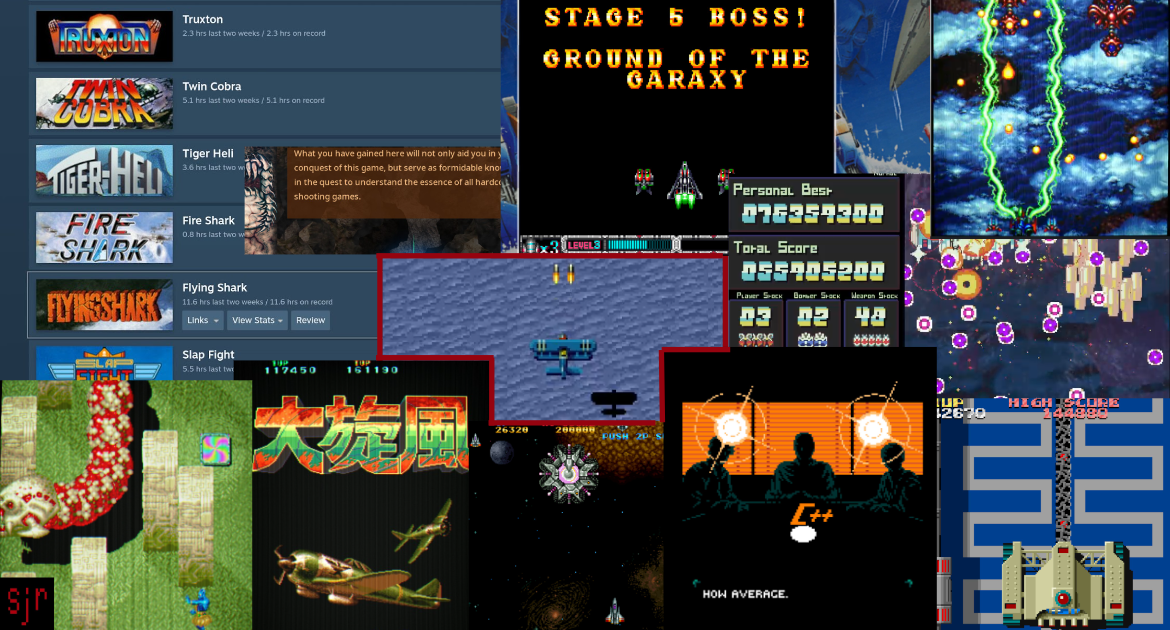

My aesthetic obessions are exacting and subject to peculiarly consistent lifespans. Predictable decay, even: there’s a hypothetical half-life here, of a hundred hours or six weeks, whichever comes first, during which intense interest in something–certain albums, films, games, or else more usually broader categories of such things–decays to a portion of its initial severity. Weeks later, only traces are left, hardly enough to sustain interest beyond the act of sporadic reflection. What once fed on my mind for six hours a day inevitably overeats. I suspected correctly, for instance, that kicking off 2025 by dabbling in the 2D shoot-em-ups Blue Revolver (2016) and ZeroRanger (2018), then becoming fixated on Mushimihesama (2004) throughout late January, playing about thirty hours of these three titles in two weeks, that I was already mid-descent down the shmup rabbit-hole, i.e., soon en route elsewhere. Combing through forum threads from ‘05, emulating arcade titles that had unlike Toaplan's, never been rereleased; importing Korean physical discs for my Playstation 5 with names so charmingly un-Anglo that even my fixation couldn’t prevent mental syllabic muddling–garrega dodon pachi daioujo ketsui kizuna jigoku tachi–and whose Japanese menus I was forced to parse individually by uploading snapshots of them to Google Translate on my phone. Making spreadsheets, systemitizing. Rotating my desktop monitor to lean precariously on its side to better mimic the vertical scrollers’ original arcade aspect ratio of 9:16. Sicko behavior, in short.

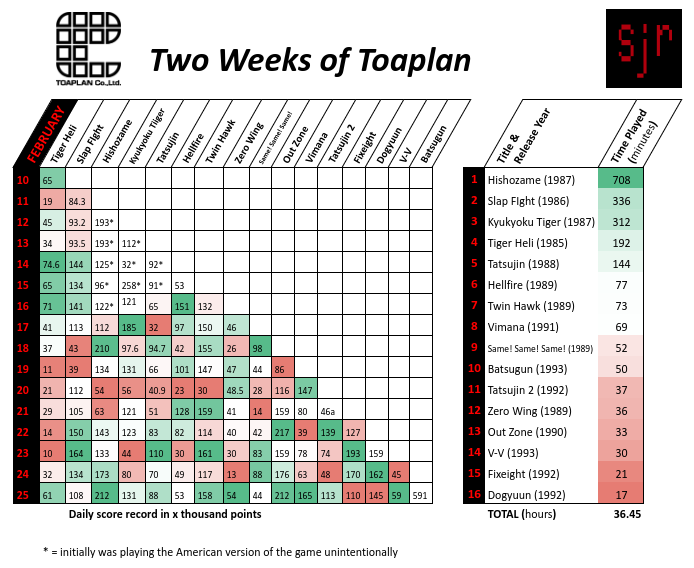

I’ve come to cherish these fickle benders, in a way, and in an attempt to nourish rather than suppress my character I often impose structural games upon the objects of hundred-hour affection. Games are the most elevated form of investigation, so says Einstein, so intimates the likes of Bombadil or Bokonon; to properly investigate games thus requires a metagame, a game containing many others, and I would prefer to craft one myself rather than conform to an existing one, given our limp default of corporate achievement systems. So it was mid-shmup-splurge, on February 11th, 2025, that I impulsively purchased Toaplan’s entire shoot-em-up catalog and opted to drip-feed myself one title each every day for two weeks, a cascading approach to this vertical slice of the canon–the metagame being to attempt, each subsequent day, to beat my own previous high scores.

Day one of my 2WOT metagame I played Toaplan’s first shmup, Tiger Heli (1985), and day two I played Tiger Heli and Slap Fight (1986), and on the sixteenth day I played those two and another fourteen games, too, ending with Batsugun (1993), and logging my daily top score for each title after putting at least one attempt in all of them. Sixteen games for the paltry sum of USD $50.90, or 204 quarters, which in decades past I would have had to slot one by one into the coin-operated cabinets upon which they originated, in exchange for credits of play, in bars and bowling alleys and supermarkets; thirteen quarters each might have bought me an hour, probably less–these are fiendishly difficult games. During my two weeks I occasionally tally up the “quarters” that could have been, hitting, on a particularly bender-y evening, 97 tally marks, $24.75 in the late ‘80s, nearly 70 bucks with inflation; precisely the cost of one contemporary game. Even while I kept to the rules of my metagame, I sunk the majority of my hundreds of figurative quarters into Hishozame, preferring it initially within, but later because of and beyond, this Toaplan context. Initially I'd been most interested in tracing the design patterns that would result in the era- and subgenre-defining Batsugun, i.e., the first bullet hell game–whose rushed arcade release appropriately coincided with my own premature birth, in December 1993, brother–but one has to adjust for one's unexpected interests. No 2WOT metagame, no Hishozame 1CC.

Modern gaming platforms log individual hours played with unnerving accuracy. I know, for instance, not only that I have played my favorite game of all time, N++ (2015), for 280 hours, i.e. eleven full days throughout the last decade, but how that time was divided by platform, 154.3, 72.5, and 53.95 hours each on iMac/PC, Playstation 4/5, and Nintendo Switch, respectively, having purchased the game three times to enjoy in different contexts of life. I know that in the 46 days following its release on September 18th, 2024, I played 163.8 hours of recent favorite UFO 50 (2024), averaging over 3.5 hours per day; I know that I’ve spent 263 hours on developer Fromsoft’s Dark Souls trilogy, in addition to 192 and 236 on their Bloodborne and Elden Ring properties, respectively; I know that I’ve logged more than 12 hours each of Final Fantasies I, IV, VII, X, XII, XVI. I know that by some strange coincidence I spent exactly 252 hours in both the years of 2024 and 2023 playing these games and many more on my Playstation 5, specifically, following 463 hours in 2022; I’m glad not to have screenshotted summaries for the ultra-housebound ‘20 & ‘21. Mostly, I don’t want to reacquaint myself with the figure for my time spent on World of Warcraft’s second, sixth, and seventh expansions during high school and after grad school, better measured in days than hours, a true heroin habit relative to the rest of these little evening indulgences.

So I know that I cannot in good faith recommend shoot-em-ups as a medium entrypoint, and I know that during 2WOT I spent 36.45 hours on their sixteen shmups in addition to another 61.7, throughout January and February, on R-Type (1987), Battle Garegga (1996), Radiant Silvergun (1998), Ikaruga (2001), Mushihimesama (2004), BLUE REVOLVER (2016), and ZeroRanger (2018). Consistent obsessions. Six weeks or a hundred hours: whichever comes first.

Given these spent hours of sore-wristed, cross-eyed free time, it probably goes without being said that I find shoot-em-ups to be worthy of such intensive study, that I like everything about these games. I like their purity. Shmups live and die by their encounter design, given their interactivity is largely limited to the protozoal act of moving a small avatar around a flat, scrolling field. Those environments are often deceptively multi-layered, with players forced to account for what’s “below” them even as that layer might pose a lesser threat than the elements with which one can actually collide. Given the ground terrain informs the routes of tanks and boats, there’s a strategic imperative to mentally map roads, rivers, and other entrypoints even while flying “above” them. This necessity of reading the terrain can lend a visually minimalist environment a surprising sense of place; it also runs counter to the passivity that might otherwise accompany the interactive act of scrolling, one which this genre is built around but which we’ve become increasingly familiar with in the very different context of thumbing down vertical scroll-based feeds of text posts, images, and short-form videos on our laptops and mobile devices–devices which, again, have subsumed the hardware on which such content originated, at great cost. In fact, vertically-scrolling shoot-em-ups, classic & danmaku alike, offer players a dialogue–a zen kōan, even–through which to reject the very practice of doomscrolling, to exchange a capitalistically-determined personalized algorithm of ephemeral user-made content for a fixed set of creative visual elements–a continuously unfurling “scroll” closer to its original papyrul connotation–to which one must repetitiously submit their full concentration, honing more than any micro-test of reactive skill a macro-test of one’s senses of calm and acceptance. As tests of high-reflex pattern recognition and thoughtful memorization, perhaps their most demanded player skill is the ability to improvisationally replicate a huge variety and number of fastidious movement sequences. It’s for this reason that they are readymade for flow states, and one irony here is that their visual language–of “bullets” and “explosions”–suggests, to spectators, a combative chaos that doesn’t necessarily survive its own mastery.

For those who can consistently enter such trances, the sensation is far less combative than it is rhythmic, and I like failing the mental dance. That studying the combination of aimed or set patterns of fire from such enemies eventually results in a recipe for movement unique to the situation, that the difficulty comes not from accounting for one pattern but several of them simultanously, and that any thinking person would be shocked, I suspect, by the combination of visual and sonic cues from which their mind can learn and combine specific reactions and behaviors, not just the resultant aesthetic value of these ultimately human-made gauntlets but the total personalized immersion that comes to accompany a successful mental-muscle performance against their flurries of elements. The shoot-em-up genre may have trended historically towards its own abstraction, increasingly trading vaguely realistic depictions of biplane & helicopter warfare in the ‘80s for danmaku’s chaotic, screen-dominating “bullet hell” post-Batsugun in the ‘90s, with the pattern memorization needed to maneuver between the latter’s cascading fireworks of death-pixel vomit taken to absurd, hyperbolic extremes, but I like that the central allure–of tracking safe space, mitigating hazards in order of risk, balancing screen-clearing resources–never fundamentally changed between those eras of design.

These remained games of triage and momentum–given small errors can snowball to failure just as easily as small successes can to victory–and I like that the resultant tightrope-walk of each 1CC exercise tests, more than anything, my non-simulated ability to function under simulated pressure: not the heartrate spike, but the six-minute performance which follows it. I like how, following one’s familiarization and success, these games evolve into abstractions of themselves, not trivial programmatic parlor tricks but mechanisms dictated by entities with fixed courses of movement which behave identically under infinite circumstances, which were designed surgically and consummately by specialized artisans who went on to pollinate other genres, games which have outlived their initial context and have come to be closely guarded by an active network of enthusiasts who believe, quite unironically and earnestly, that within some of them lies a kind of enlightenment.

This is an excerpt from a longer in-progress work.