Sugoi

On Downwell's narcotic flow state.

I’d picked Downwell (2015) back up due to a recent interest in 2D games focused on verticality: the gravity-flipping of VVVVVV (2010), specifically, had led me to thinking a lot about the particular mental sensations of interactive descent. Downwell is a game about falling down a very deep hole, falling for about ten minutes, all the while shooting but mostly bouncing off of frogs and skeletons, pointy squid and lovecraftian void fragments; it’s limited to three inputs and a minimalist aesthetic, both of which enable a deceptive complexity, since entities onscreen & proper responses to them can be interpreted and triggered by the player more quickly when their signals are spare. I reasoned that I might be able to read these strange, experimental platformers against each other, preoccupied as they each are with gravitational play within an abstracted, voidlike environment.

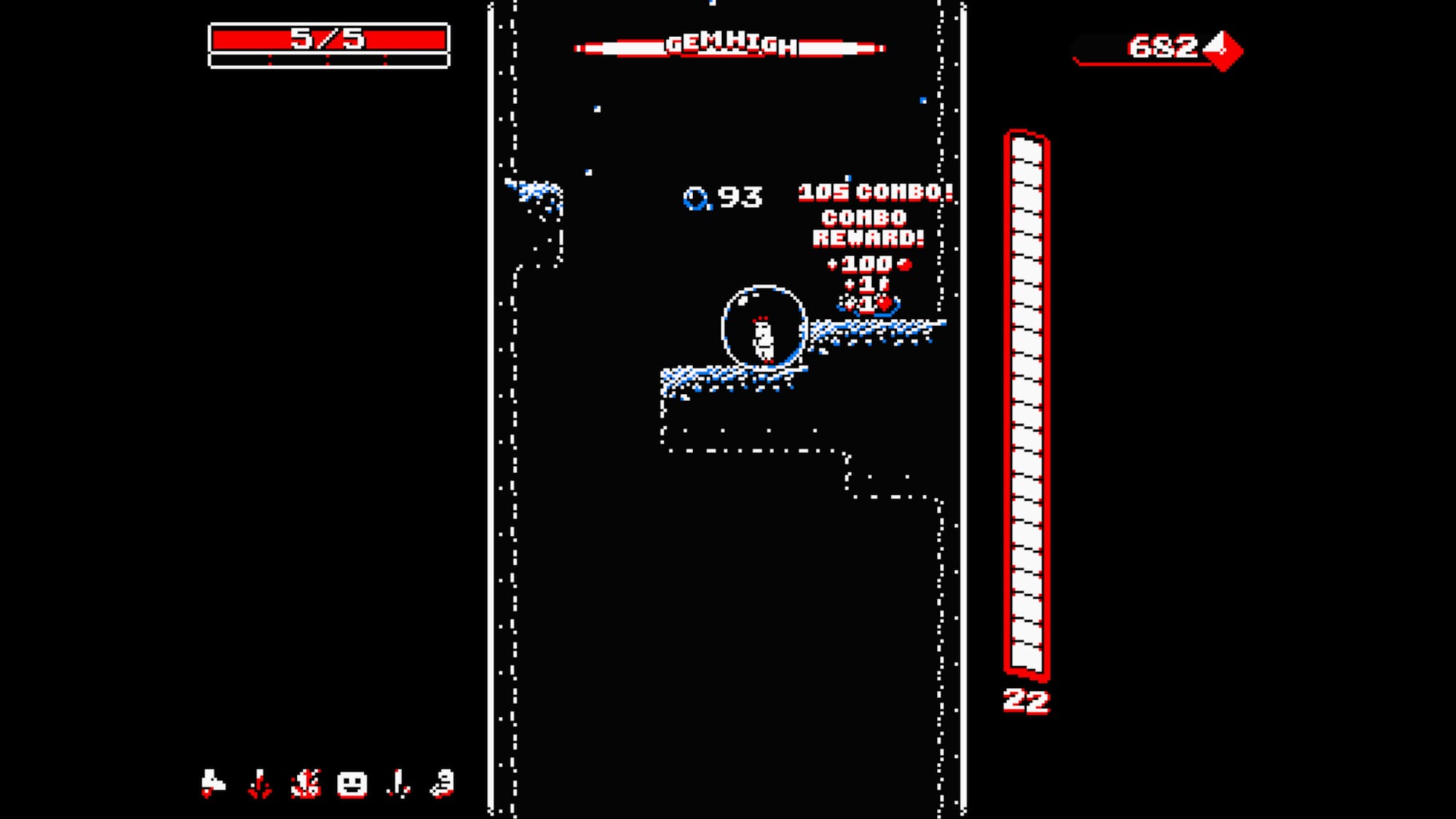

Ultimately, in the case of Downwell I became more interested in the void. Not just the subterranean nightmare waiting in the monochromatic vacuum of space which lies below its caverns, catacombs, aquifer, and limbo sections, mind you, but the actual sensation of lack, the emptiness which confronted me upon reaching the end of a gauntlet which at one point had felt endless, a spent addiction to the fleeting interactive sensation of falling forever. That sensation is grounded in a much game-ier system of progression, of course. Health and ammo upgrades are granted upon combo-ing a certain number of enemy bounce-kills without actually landing on any of the fixed platforms jutting out of the sides of the well. If you’ve ever tried to leapfrog between the noggins of several Goombas in Super Mario Brothers, picture Downwell as a game-length version of that idiosyncratic digital high, a kind of agentic wish fullfilment for skipping rocks or ping pong trickshot compilations. I soon became less interested in actually beating the game–by reaching the terminal point at the bottom of level ten–than I did in racking up increasingly large, pinball-bumper combos of descent, a juggling ritual which repeatedly stupefied my mind-thumbs interactivity-apparatus into impossibly deep states of zen-like focus.

Oddly, and as other commentators have pointed out, one quirk of the system here is that the game’s win-state directly incentivizes players to end combos relatively early: bonus utility items–extra gems, ammo, and health upgrades–don’t continue to scale up after chaining 25 kills together. The only extrinsic motivator for doing so is an achievement called “Sugoi Combo," just one of our medium’s infamously nondiegetic in-game pop-ups which would lend me, for one small moment, the rote catharsis inherent to the completion of a wholly arbitrary interactive challenge.

I’ve come to a name for this specific brand of hyper-addicting objective– mousetraps–for the way my brain gets caught on them like a rat in a labyrinth. Having a lifelong draw towards single-player computer games and platformer games specifically, VVVVVV’s collectibles, Celeste’s C-Side levels, and the Sugoi Combo here each have posed particularly intense fixations, guantlets which were alluring precisely because they demanded multiple hours of rigid, though highly satisfying, concentration, but which were ultimately ancillary to “playing” the game. We tend to observe the effects of addiction in the longterm, the weeks or months spent in binge-restrict patterns adding up to something greater (lesser?) than the sum of unfortunate parts. But I’ve always felt the bite of a digital bender to be most severe during one-time, sustained sessions spent in pursuit of a result which obviously doesn’t equate to much back in reality–in effect only ever a memory that is itself mediated–but one which doesn’t even necessarily constitute the primary forms of progression, or fun, within the game.

Regardless of mutual mediation & couchlock, mousetraps are distinct from the numbing sensations of a substance high in that they are contingent upon the perception and realization of an end-state which is difficult for users to bring to fruition, whether due to tactical understanding, reflex-based play, time commitment, or a combination of all three. Sugoi–an informal compliment in Japanese used to express admiration or amazement–is actually a proper adjective for the mastery over Downwell’s interlocking systems required to land a 100+ combo, the awareness and accounting, mid-descent, of so many variances in weapon type, power-ups, enemy behavior, and level hazards, which must be read in advance, like sheet music. There’s an irony latent to Sugoi Combo’s framing–it being a reactive pat on the back (“wow!”) to the same behavior that it has itself prompted–which applies to most of gaming’s “achievement” systems: the primary motivating factor is meta-textual, totally independent from the actual feedback loop of systems which form the computer game. A human-made mechanism placed in an otherwise natural environment, traps for attention which can kill the simulation by itself. Though I didn’t put Downwell down for good while mainlining Sugoi attempts, I very well might have.

One need only study the glut of cross-game achievement systems which Valve, Sony (trophies), and Microsoft (gamerscore) have developed for their respective platforms to see first-hand a) the degree to which many players, like myself, will modify in-game experiences totally in accordance with arbitrary objectives, some even going so far as to self-select out of playing any title which lacks an achievement list, and b) the degree to which many game developers appear unaware of or else unengaged with this phenomenon. My contention has always been that such systems are a largely unmined reserve of experiential diamonds unique to our youngest artistic medium. At their best, such extrinsic trappings function not as binds but as byways: alternate methods of progression which signal ways for players to play more creatively or else better understand a game’s systems, but still reach its natural end-state(s) by doing so. (See, for instance, the rabidity with which player discourse centralizes around which achievements are “missable” and “unmissable.”) Sugoi Combo is among the strangest examples I’ve come across, in that it straddles the intrinsic and extrinsic motivational modes of the game, simultaneously provoking a way of playing Downwell that is all at once more natural, fun, and difficult than reaching the bottom of the well, but also somewhat mutually exclusive with that goal. Once I’d Sugoi’d, Downwell had no extrinsic motivators left for me, but the intrinsic spark was also absent: I didn’t feel like mastering its systems any further. Upon reaching the bottom of the well a couple of runs later, I snapped out of its narcotic flow state, electing to move on to other places, other pits.