Nilbog

Two by David Szymanski.

Consider an hour-long computer game about stabbing goblins in the face with an antique dagger, a one-sitting bout which begins in the museum basement from which the squat bastards escaped, from which the weapon of choice was also pilfered, and admire the way this exercise is sustained by playfulness but never laziness, not a mean joke but wit relayed earnestly, its narratively- & architecturally-varied three-dimensional simulated spaces so reminiscent of the better work by our first person shooter scene’s ‘90’s “mappers”–e.g. John Romero, Sandy Peterson, and American McGee of Doom and Quake fame–that the garish goblin massacre becomes a righteous anachronism, actually, purchased for $4.99 & launched noncommittally at ten p.m. on a weeknight as it may have been, something to be taken seriously, in fact.

Chop Goblins (2022) developer David Szymanski bills his game as a “microshooter,” not even necessarily the high-water mark of an increasingly impressive career in interactive brevity. I first came across his stuff by way of another micro-title he’d released only six months prior to Chop Goblins, one I’d likewise binged impulsively in a late-night sitting but for markedly different reasons. Iron Lung (2022) is set entirely within the confines of a one-room vessel submerged in a blood ocean on the surface of a lightless galaxy’s unexplored moon; the gameplay loop consists entirely of tinkering with the vessel’s positional x- and y- coordinates in order to snap grainy photographs of its surroundings. In-game, I documented the points of interest on behalf of an unseen prison state, an experience elicited by and contained within the frantic shadenfraude accompanying a three-day bender–in reality–of the news coverage and discourse surrounding the June 2023 implosion of OceanGate’s Titan submersible, a vessel made from, and perhaps in part destroyed due to, consumer-grade cost-cutting & regulation-skirting hardware such as the $30 Logitech game controller with which it was steered, a device twice as cheap as the one with which I completed both of Szymanski’s excellent computer games, incidentally. We all knew, of course, that the five occupants onboard were already dead; the sicko allure came with imagining in great detail the low-probability scenarios in which they somehow were not, the stuffy billionaire panic, and–concurrently with less explosive news across the globe that the Greek coast guard had been throwing dozens of migrants overboard into the Mediterranean, resulting in their horrific deaths, obviously–while my tax dollars were being guzzled up in a multinationally coordinated effort to rapidly locate the compacted body-mist-fragments of several dipshit entrepreneurs, I got a midnight contact high from the oxygen meter depletion beeps that Iron Lung sent reverberating through my noise-canceling headphones.

The game pulls an interesting trick of inference. Since the vessel has no windows, with its exterior only ever discernible via the results of a camera mechanic which are both hyper-delayed and low-fidelity, the player is forced into imagining nearly the entirety of the game’s environment. This has a very curious effect on the brain. The polygonal walls of the sub itself aren’t exactly photorealistic, but by merely presenting a second theoretical environment–one inaccessible via the game’s primary modes of movement and sight–the experience has in effect been doubly mediated, one process of first-person documentation contained within another–grainy photographs on-screen within a submarine on-screen within reality–each more palpably real not despite their relative simulacral distance but because of it.

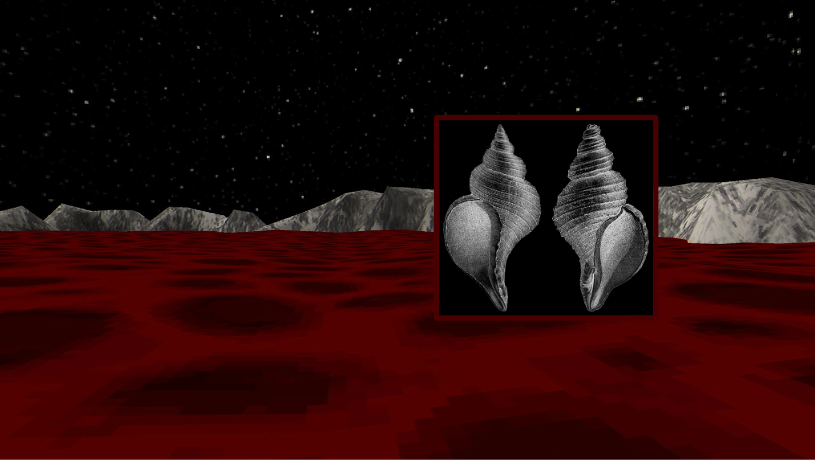

Or: orienting the sub’s coordinates against a graph of bracketed sites while accounting for the unseen walls of the scarlet trench is scary, for sure, but only because it offers a robust simulation of partial blindness, of walking through any unfamiliar place without your sight. Such navigation wears on the psyche in direct proportion to one’s suspension of disbelief, to the faith placed in an imaginary place and more specifically in one’s own mental rendering of its claustrophobic boundaries. Or lack thereof: the scariest parts of the game occur when you think you’re going to come up against a boundary, a noise, a signal, but do not. If, throughout Iron Lung, it slowly becomes clear that you are not alone in the depths, that your indentured photography is a corporate attempt to document the existence of some submerged beast, then I’d wager the thing that eventually appears onscreen–jump scare!–is far less frightening than the one you’ll imagine. The photography mechanic becomes an elegant bridge between twin leviathans, one digital and the other mental, the first a necessary proxy for the second, neither of which are “real” in any traditional sense of the word. I found myself lingering on my own leviathan–giving the memory its oxygen of mental attention–while, many months later, I was more numbly eradicating Szymanski’s cleaver-wielding gremlins by the hundreds. Like all good games, Chop Goblins is not really over once it is over, with several endgame modifiers that only become available after the first clear. Nilbog mode, for instance, is the game’s mirror mode–get it?–an axis flip which not only applies to level geometry but also to the player character’s handedness: the dagger once held in the left hand onscreen is now held in the right, but the stab button remains unchanged, a tweak which so thoroughly destabilizes the game’s simplistic feedback loop that I felt briefly as if my own sense of relative direction in the real-word had become knotted up, cross-eyed. Human hands being our readymade example for chirality, I begin, now, to read up on the sinistral & dextral, and come across an extinct species of sea snail–Neptunea angulata–whose shells’ directional coils were not only varied–unusual within a single species of gastropod–but dependent upon their hemisphere of origin, spiraling left in the oceans of the south, right in the north. Squinting at an 1878 illustration of the extinct mirrored phenomenon, several disconnected perceptions drift languidly through my mind, disconnected points–that populational splits of roughly ninety-ten are shared by right-handed humans and right-coiled gastropods, that such shells grow concentrically outward, like tree trunks, until the animal inside dies, leaving the spiraling bio-edifices to decay into fragments, eventually into the sand which settles at the bottom of trenches–and counterpoints–that the existence of any mirroring suggests a hypothetical point upon which both sides pivot, a pane of glass, a computer screen–my tangential approach towards, my non-contact with, the undersea primordial by way of doubly mediated photography or internetworked encyclopedic image-scanning imparting an uncanny sense of embeddedness, a layering of histories, clapped memories, sub-realities which now fan back outward, the leviathan making its way back to me.