Barbuta

An alternate past for the nonlinear action platformer.

One of the most left field interactive experiences you can have this year is an action platformer made to look and play as if it predates the original Metroid (1986) by several years. Its retro pedigree is so convincing that I’m hesitant to use the genre affix of the same name which we’ve agreed upon for this particular kind of game, one which features guided nonlinearity and utility-gated exploration and which is often, but not definitionally, also an action platformer: Barbuta (2024) is less “metroidvania” than anachronistic fossil, a puzzle stuck out of time. By proposing an alternate past for this particular strain of computer games it of course proposes an alternate present, in which the ensuing lineage of titles focused on 2D exploration evolved out of a more esoteric and brutal template.

Barbuta is wonderfully-chessboard sized, confined in its entirety to a fixed eight-by-eight grid of rooms displayed at all times in the bottom left corner of the screen. I found myself using chess notation to memorize landmarks: grab the coin at D5 for the shop at B3. The directional pad moves your player character, a humble knight–”barbute” being a type of 15th-century Italian helmet–through a graph-paper castle, and very, very slowly at that. Two other inputs allow you to A) jump and B) attack. That’s it: the “action” on screen is as reminiscent of the later years of the Atari 2600 as the early years of the NES/Famicom.

The resonance of such a masochistically old-school exercise will of course be commensurate with not how well it mimics the hard- & software of old but by how cleverly it works within such creative constraints, namely, by recontextualizing its patient (read: punishing) movement within a series of interconnected lock-and-key obstacles which have not only been cleverly hidden in plain sight but which can be completed in a number of different permutations. If the rooms each sit upon a chessboard square, then sequences of them are, appropriately, like "lines" in chess, alternate branching paths of play which need to be accounted for especially because they lead to non-identical gamestates which appear deceptively similar. The irony of this subgenre being that meandering linearity so easily masquerades as actual exploration: a single chain of objectives containing fixed backtracking sequences is still a single chain. Not so here. Barbuta, (fictionally) released in 1982, is as much proto-Maze of Galious (1987) as proto-Metroid (1986), if you know your stuff. And for my money the epiphanies-per-minute latent to the best work in this medium have rarely been as consistent, capsulized, or satisfying as they are here.

Barbuta will show its hand immediately. Upon following your arcade-monkey-brain impulse to move immediately right upon hitting START, a portion of the ceiling will collapse on you and leave you with five of six lives left, with no continues to be found here once those lives are gone. Thank god: a hard restart means you’ll be inclined to study any failure more closely, and may even notice that it wasn’t by random chance that the ceiling fell, but your contact with a pixelated block of granite that looks slightly different than the rest.

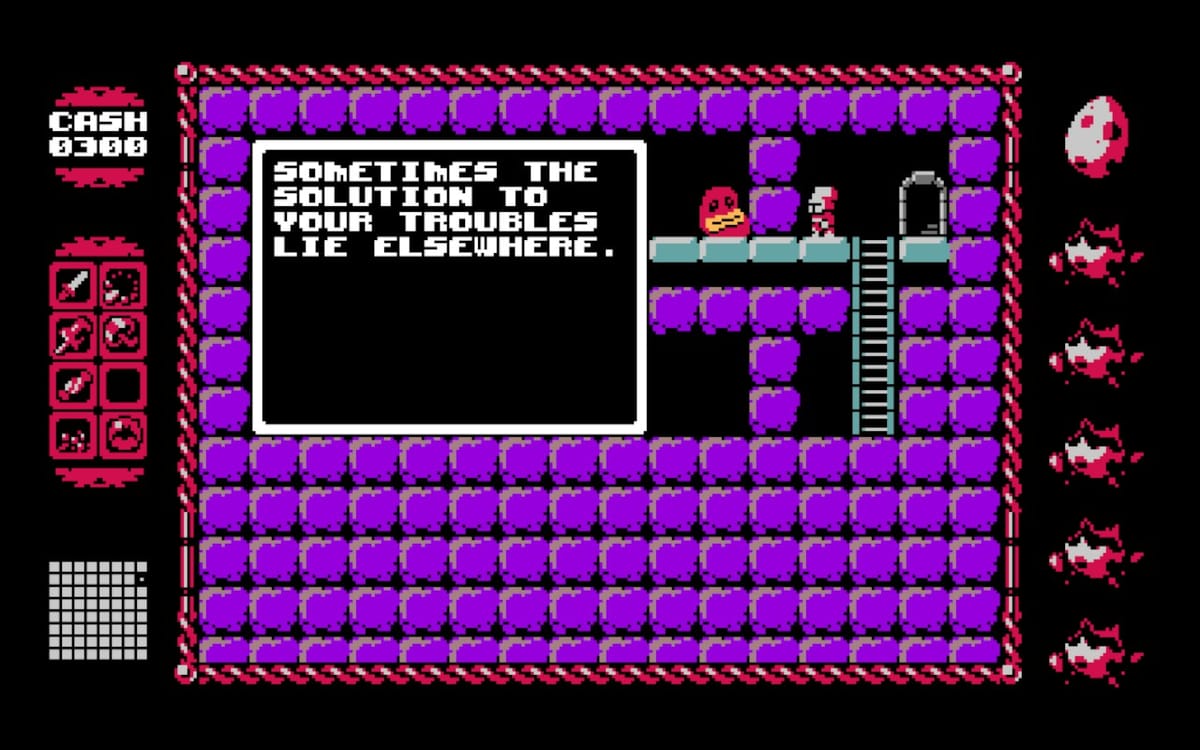

Barbuta is kind of a game about traps, about the rituals of observation required to avoid them. But to frame it as such is to ignore all the ways in which the game strives to trick you less diegetically, by presenting obstacles that exist not for our fictional 2D knight but for the human controlling him offscreen. “Welcome to my home!”, a gelatinous non-player character chirps, “If you wish to make any headway here, keep an eye out for anything out of the norm.” Barbuta’s talent is not in traps but illusions: it plays tricks with our tendency to sight-read the building blocks of levels as identical when they may not be, with our preference to move between room-screens via only the most obvious paths–with, most of all, our habit of navigating labyrinths impatiently, like rats. In doing so it offers a special, rare kind of maze, as much a proxy for a physical place which can’t & won’t exist as it is a grander, ticking mechanism–something more human. If you study it closely, tracing your way to its central chamber, you will certainly come to feel and delight in the intellect behind it; if you prefer brute force, you will surely abandon this place, as it is not one that reveals itself to those who beeline between dead-ends. Nor to those who ask others to show them the way.